If there is one thing in this world I hate, it’s losers. I despise them.

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Our world is a reality of untapped opportunities and missed chances.

Transformations? Pandemics? Revolutions? Not here. Maybe somewhere nearby — in the next village, beyond the meadow, the river, and Snake Mountain. In some parallel dimension where that better world is unfolding — the one where people are prettier, governments fairer, and, well, the grass is greener.

In their book The Dawn of Everything, the two Davids (Graeber and Wengrow) attempt to trace when, in human history, social inequality emerged. In other words, when did we miss our chance to live as a horizontal society — one without material ownership, war, or despots?

Was that ever part of our history, or the history of our forebears, their postures bent under the force of gravity and their faces resembling a Fiat Multipla? Perhaps people have always been wicked, and there was never such a thing as the ‘beginning’ of injustice. Maybe the middle name of our reality is injustice — whether you are a speck of cosmic dust spinning through space, a minority being exterminated, or a tree to which a dreadlocked activist is chaining himself.

Did the two Davids manage to uncover the origins of that unfortunate human trait that I will sum up as: a man never misses an opportunity to strike? I am not sure. Their several-kilo tome outweighed my reader enthusiasm. What remained after the reading were the astonishing accounts of how the relatively horizontal North American societies criticised the European invaders for their materialism and obsession with hierarchy – and how those invaders repaid the criticism, I suppose I do not need to remind you.

As if that were not enough, let me throw in another book: Another Now: Dispatches from an Alternative Present by former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis. In it, he writes about the missed opportunity of the crisis that followed the bursting of the US housing bubble in 2008. If the media world in which I live only really began after the fall of the Twin Towers on September 11th, then the concept of late capitalism was born in the painful throes of that very crisis. What followed were the Indignados and Occupy movements and, with them, a chance to fundamentally change a world ruled by money – a chance that, as you might guess, was squandered.

Remember the sense of zero gravity that came over us in 2020 as the Covid-19 pandemic spread? The spring lockdown, the yeast shortage in the shops, the allotment garden craze, and those endless hours spent Zooming in front of the screen? Let him who remembers that time only with dread be the first to cast a stone. A moment to breathe. Empty city streets. Condensed reality. Social distancing. And the overwhelming fear of the virus. Who remembers those sweet, empty promises — that nothing would ever be the same again after the pandemic — swept away by summer, and then another summer, and then inflation, war, October 7th, and on and on?

Deep.

It was one of those long-awaited bright days that come after the cold months – when the city streets fill with people, the air smells of earth and sunlight, and the world grins at you like you are at the start of an acid trip: you don’t know what’s happening yet, but you already know it’s going to be fun. Yes, I love these days that come after winter, like wandering tramps, like pilgrims finding their Mecca, entering cities wrapped in the scent of flowers, cigarette smoke and children’s laughter.

It’s just a shame that instead of enjoying the day, I am lying in bed, my lymph nodes screaming to the heavens, clogged to the brim with greenish mucus. I am bedridden, sick, poisoned, writhing in the throes of what is called Integration – the process that will allow me to undergo a transformation, to evolve from a wretched human into an avatar of the second half of the 21st century: a green humanoid, a post-apocalyptic zombie of interspecies accord – in a word, an Aux.

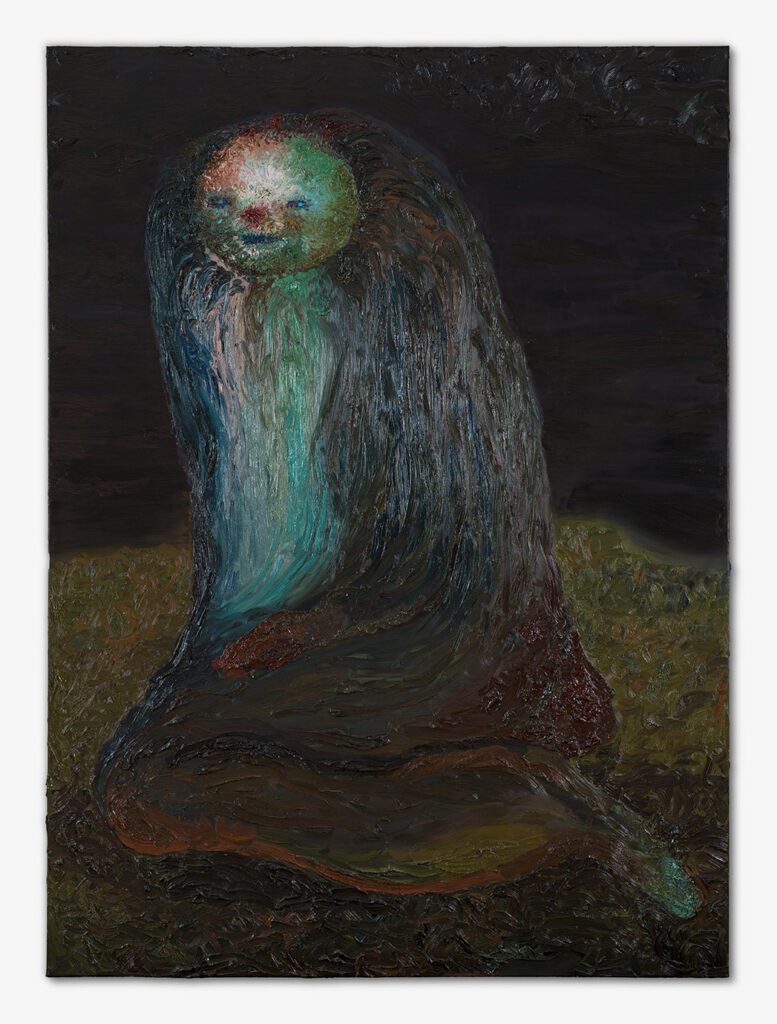

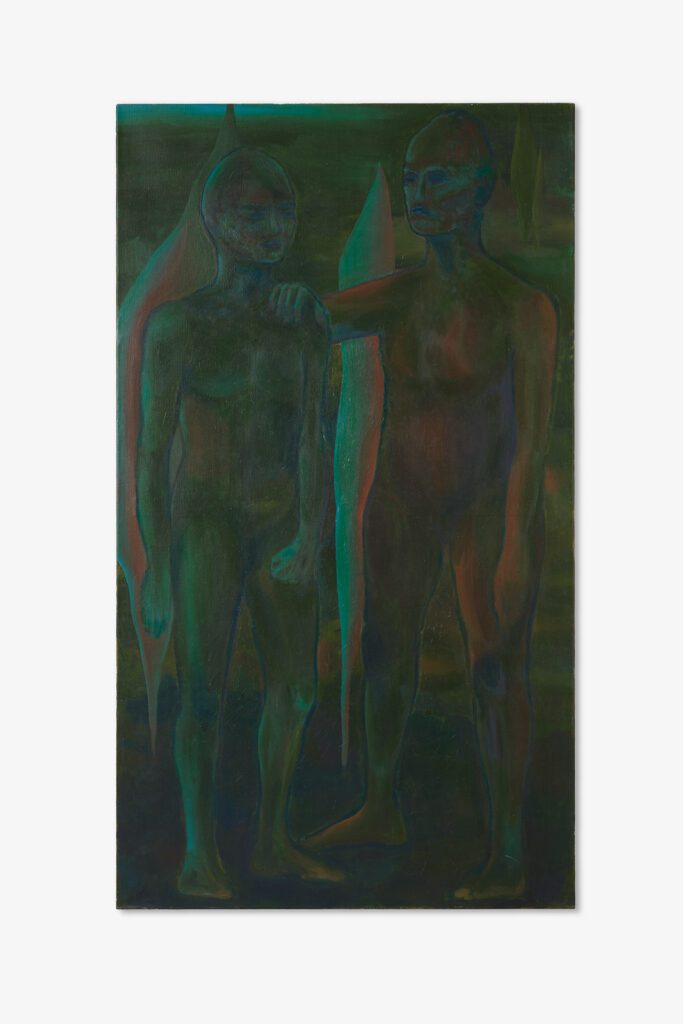

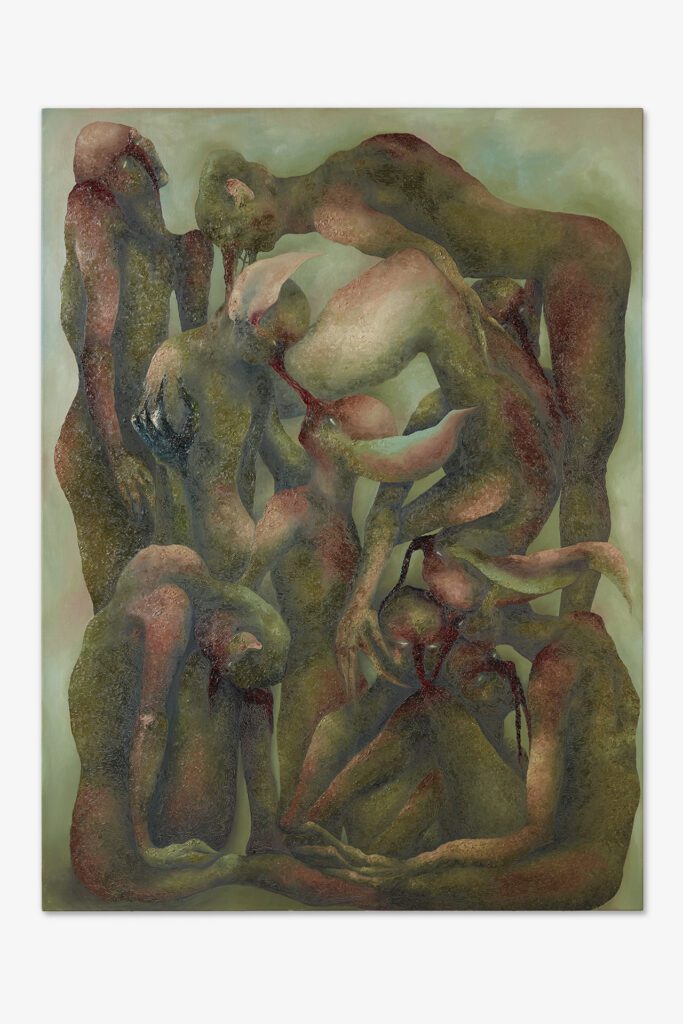

An Aux is a higher form of existence that combines the human body with plant traits. Aux is the dampness of morning soil mixed with the dust of roads once trodden by the feet of the entire human race. Aux is photosynthesis and fluids, gastric juices. Aux is blossom and head, legs and stems, roots and chakras, intertwined into something that may look like a freak from afar, but up close is nothing more than a compromise – between us and them, between the world of plants and the world of humans.

Green.

The exhibition of works by Eva Maceková, an artist from Slovakia who has lived and worked in Prague for many years, opens the gates to the reality of tomorrow. In her fantastical, brooding paintings – like legends torn from the depths of the Bohemian Forest – we discover a world of ambiguous coexistence between humans and plants. The creatures that inhabit it – the Auxes – create, communicate, vegetate, and reproduce, reluctantly allowing the curious eye of the viewer to enter their habitat. The title of the exhibition evokes a word beginning with ‘e’ – which, out of sheer contrariness, I will refrain from uttering just yet.

The world hollowed out of soft painterly matter — into which Eva invites us — is the embodiment of a vision of the future: one of radical coexistence between the animate and the so-called inanimate realms of nature. In it, we see traces of deep ecology, in which the centre of gravity shifts away from humans towards other beings, as we try – if only for a moment – to adopt their perspective and imagine what it would mean to perceive the world outside an anthropocentric frame. I know, I know – it is a doomed attempt. Even more pessimistic about human nature is the dark ecology, haunted by the spectre of ‘no future,’ which rejects any possibility of a healthy coexistence between us and others. The scenes in Maceková’s paintings do not make it entirely clear who the Auxes are – or whether they are closer to humans or some giant Venus flytrap that eats humans for breakfast. As you look at them – the Auxes, not the flytraps – I suggest you put aside the gaze of the white man on safari and, for a moment, enter the mind of Doctor Eggman, who, at the end of the first Sonic the Hedgehog film, crash-lands on a planet populated entirely by giant poisonous mushrooms.

The exhibition also includes a supplementary section – an exhibition within an exhibition – which provides a context for the Czech art scene and presents tendencies close to the artist’s heart, illustrated in media such as drawing, textiles, comics, and performance.

Appendix: Martin Pondělíček, Tomáš Motal, Iva Davidová, Michael Nosek, Marie Lukáčová

Jan Slanina’s light installation was created for Eva Macekova’s exhibition Garden of Uroboros: Organic Bodies, curated by Dominika Bernatková at Karpuchina Gallery, 2023.

Project co-financed by the City of Krakow. Projekt współfinansowany ze środków Miasta Krakowa.