I had already intended earlier to use words to describe the work of Julius Reichel, a Czech painter

whose work I came across in Krakow’s UFO Gallery, mainly because this author treats a symbol the

way it should be treated: with laughter. After all, hasn’t the symbol already obscured reality for

us? Symbols have led people into wars again and again. And a word is a symbol, too. A letter,

hehe.

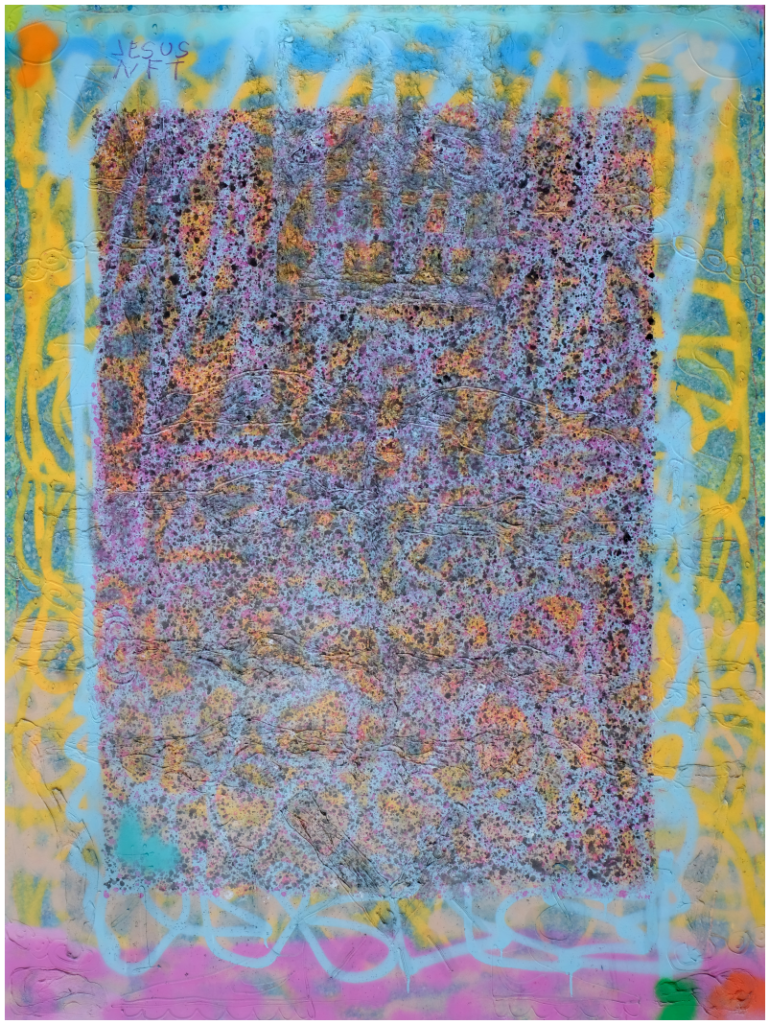

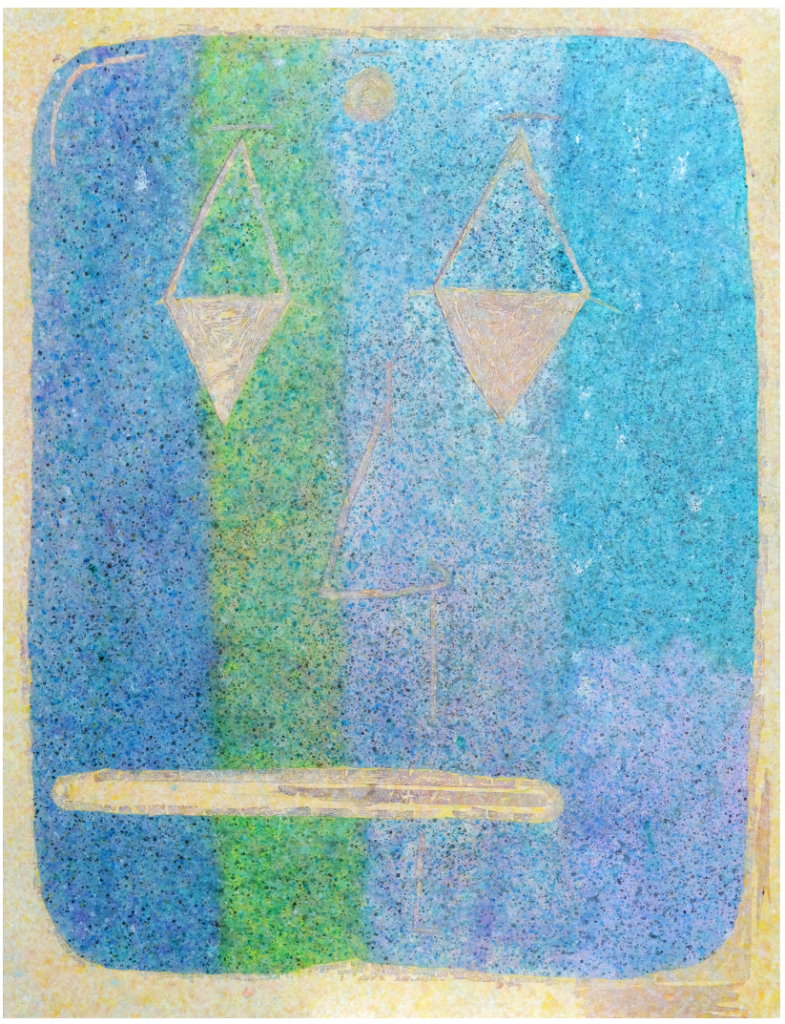

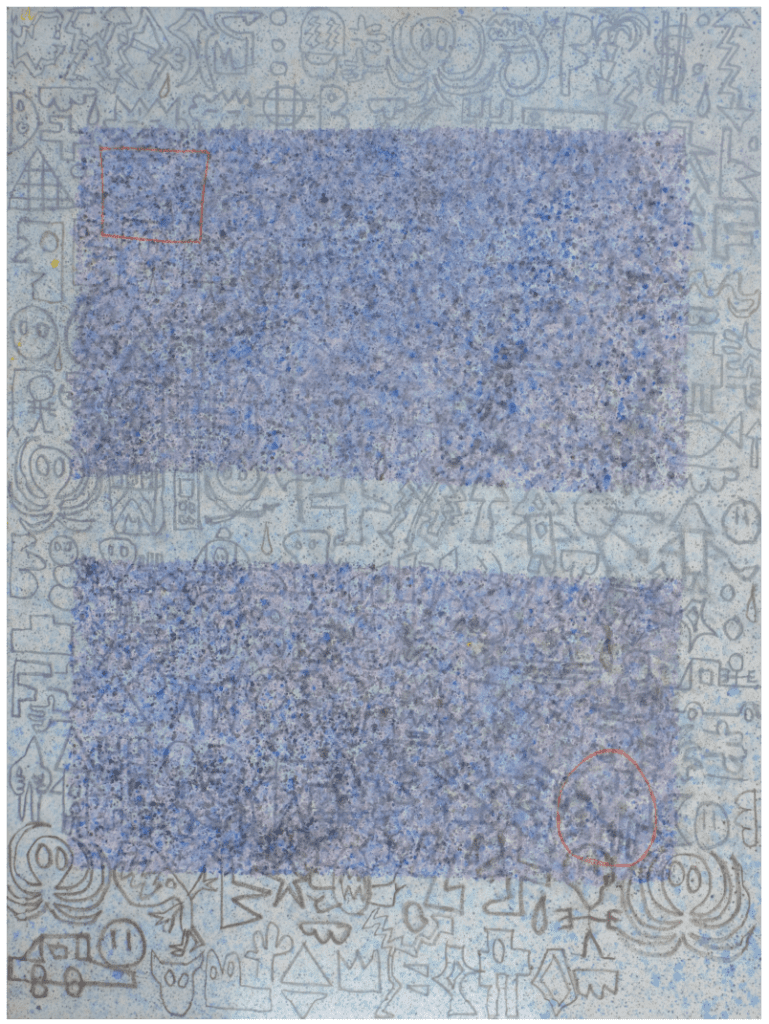

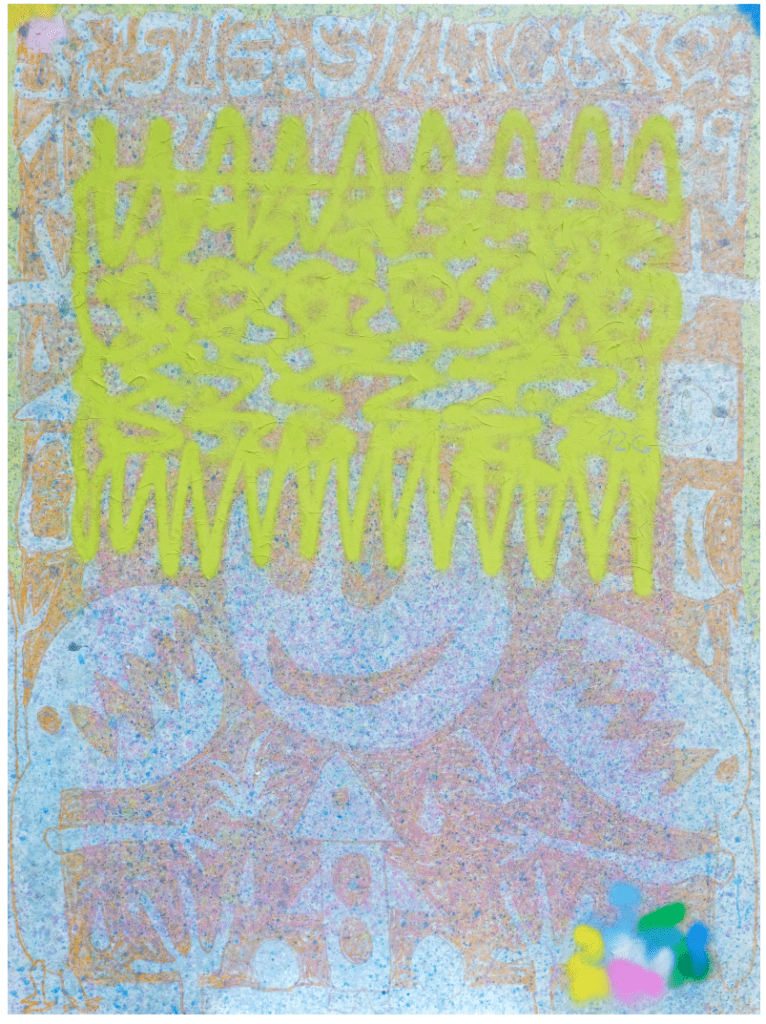

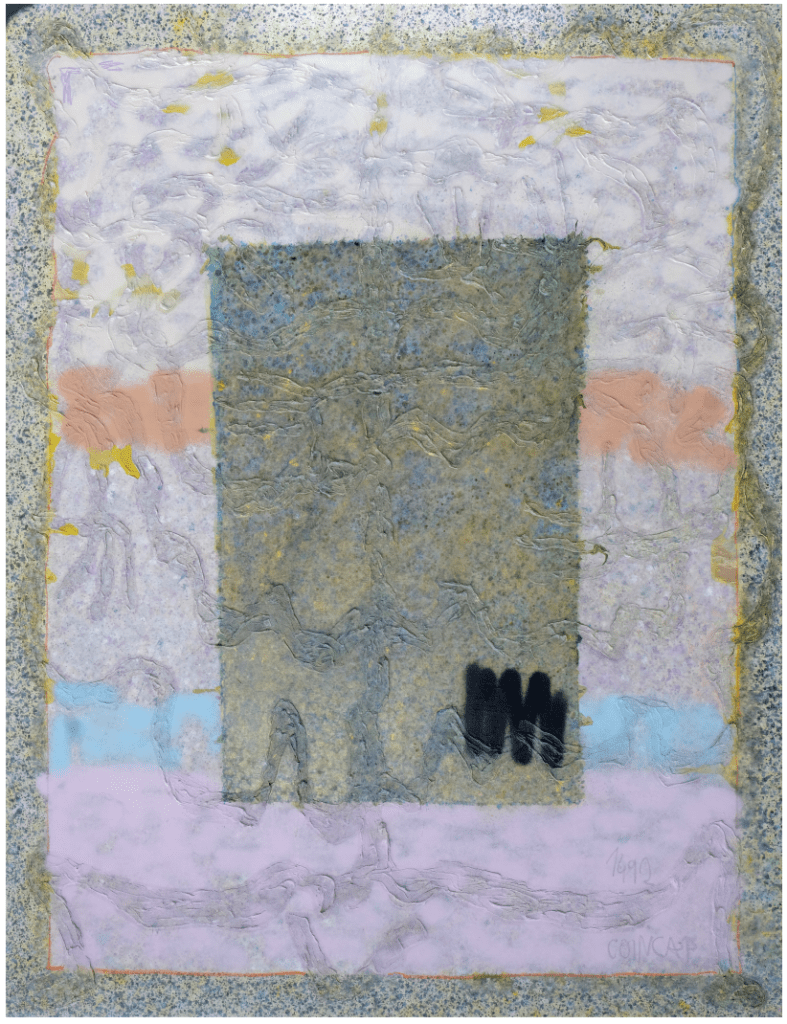

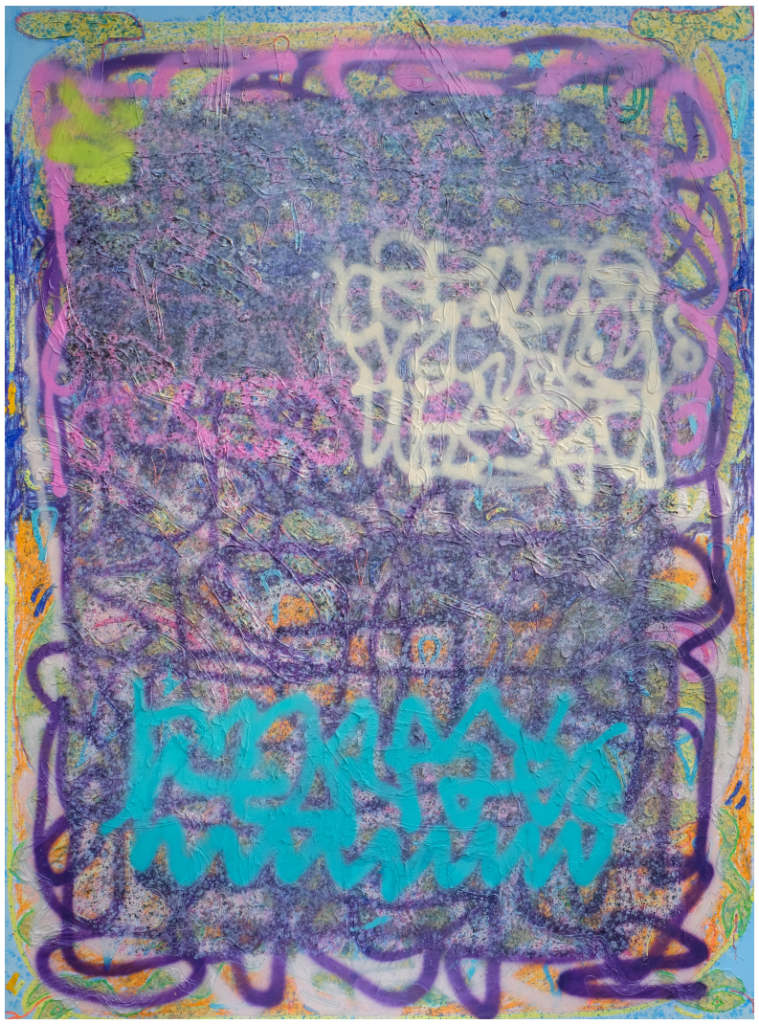

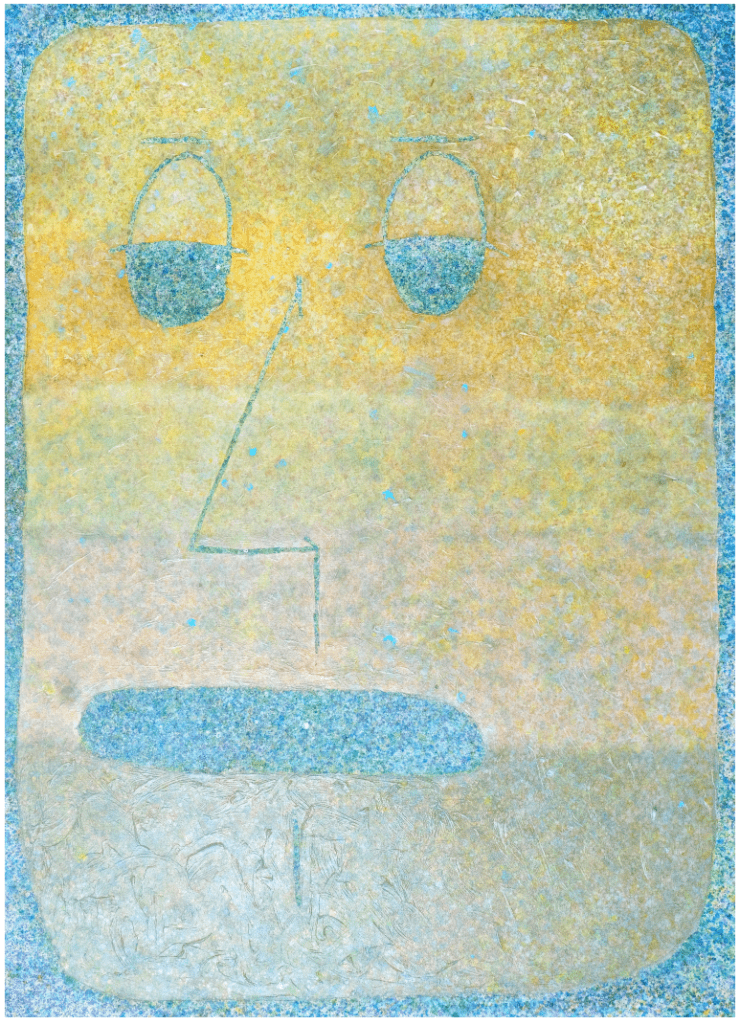

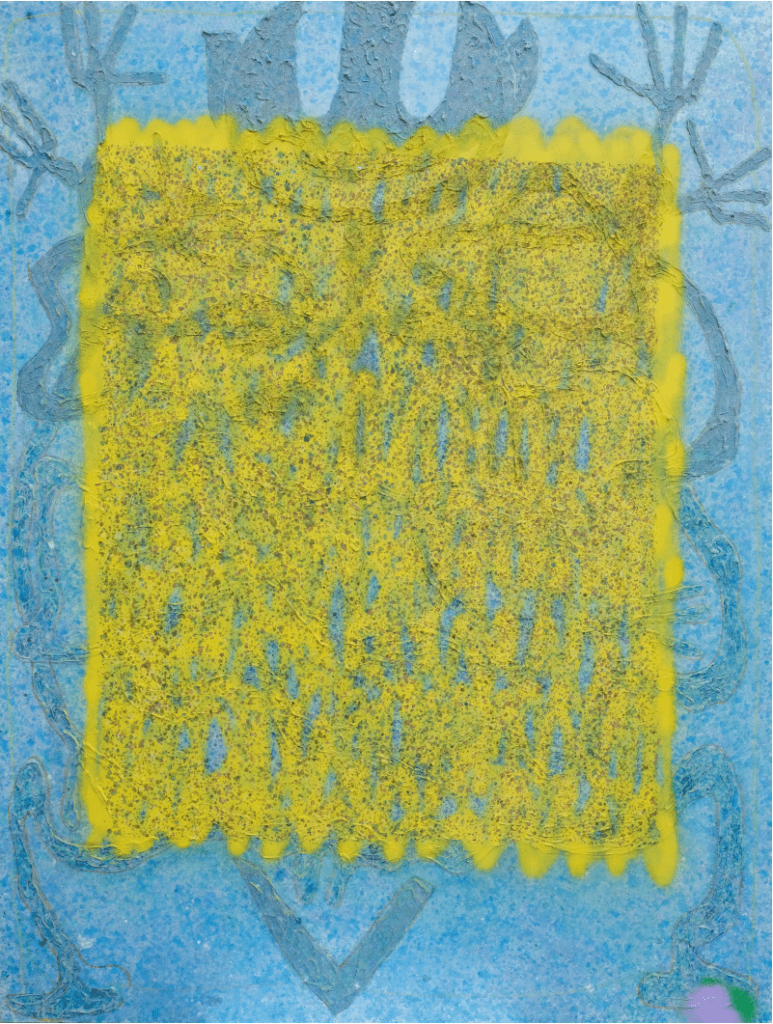

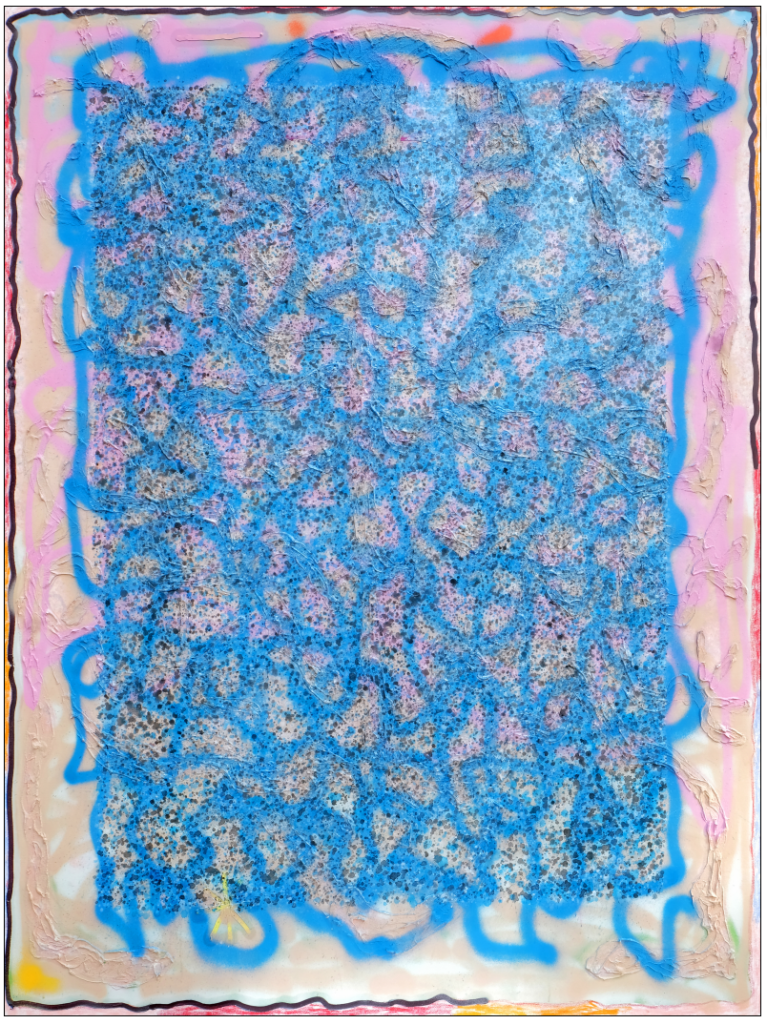

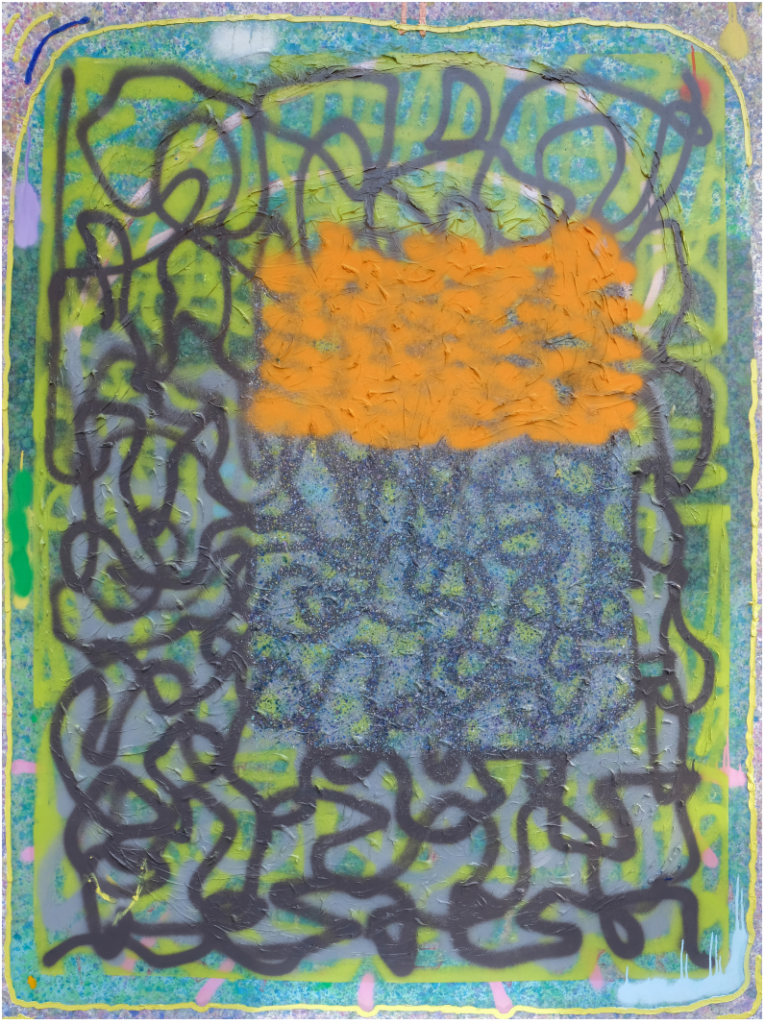

As I remember and recall, Reichel would fill his large canvases with cascades of surrealistically

arranged symbols, emoticons, hieroglyphs, pictograms, ordinary stamps, and scrawls, sometimes

in a strip composition, row after row, thus triggering several levels of interpretation of his work

and provoking the viewer’s perception into strongly historicised time spaces. The starting point for

thinking about his painting is, after all, abstractionism, and one in which the immersion in subtly

treated colour, refined colour, combined with geometric forms and the aforementioned

hieroglyphic treatment of the symbol, where it can be found and childishly treated forms,

elements of graffiti, scribbles, almost melt together into a unique, syncretic form. One can also get

the impression that the aforementioned graffiti’s reference to cave engravings, glyphs of sorts,

and wall drawings is an attempt to find freshness in the creative process, in the work itself, and

indeed in life, despite the commercial conditioning of the art market and artistic attitudes. It is a

rescue of the child in the creator.

It’s cool. You get a sense of the naturalness of the work and of the creative process, too. The

multiplicity of all these ‘signs’ on the canvas requires large formats so that this multiplicity, with its

hecticness, would resound in perception; small formats would give the impression of half-

heartedness, incompleteness.

Robert Rybicki