They say it all happened in 1869 during Whitsun in the village of Odporyszów. The villagers gathered at the church after Vespers and craned their heads high into the air. They stood, waiting, looking, some at each other rather than in the direction of the church tower, where a tiny figure would appear after a while. People spoke different things about him. Some called him the ‘peasant Icarus,’ others the ‘winged sculptor,’ while he went by the name of Jan Wnęk. He was a carpenter by profession, a young village prodigy, gifted with an extraordinary talent that did not go unnoticed. He fashioned lime wood statues of saints with sad and thoughtful faces. They could hardly have been any different, given that in his youth, Wnęk had witnessed not only the suffering of peasants but also of lords, sawn, quartered and ripped to shreds by the followers of Jakub Szela. Wnęk himself was self-taught. Once he had travelled beyond the boundaries of Odporyszów and had seen Wit Stwosz’s intricate sculptures in St. Mary’s Church in Krakow. Observing the world, he learned. When he was not working, he loved watching birds flying during the day and bats at night. He would follow them with his eyes as they cut through the sky with their delicate wings and drifted borne on air currents. It is difficult to say when Wnęk developed the yearning to fly. What is known is that at some point, he began constructing wings in his workshop. He called them ‘flights’. They were large and light, perhaps even similar to the ones that, thousands of years before, Daedalus had built for himself and his son to escape from Crete. Wnęk, however, did not seek to escape. Chances are that all he wanted was a surrogate for freedom, a desire to see the world from a different perspective. He made his first flight in 1865. Early one morning, as the harvest was beginning, he climbed to the top of one of the Seven Springs Hills and flew. Those who saw this feat later said that Wnęk’s ‘flights’ had been pulled by horses, and he glided on them like a bird. He continued his aerial escapades in the years to come. Apparently, even the newspapers of the time wrote about Wnęk’s feats, and people whispered that he did unbelievable things. It comes as no surprise that a few years later, during Whitsun, a colourful crowd gathered in front of the Odporyszów church, famous for its miracles. This was because it housed a miraculous image of the Virgin Mary, to whom Wnęk had entrusted his flight. It is not known whether, at that one moment, the Blessed Virgin was taken aback by Wnęk’s feat or whether she was preoccupied with other matters, but the man plummeted to the ground 1,350 metres from the church tower. Both the ‘flights’ he had constructed, and his bones broke and shattered. Jan Wnęk died a few days later and was buried by the same priest who had taken him to Kraków and allowed him to fly from the church tower. People, as people do, reportedly said that Wnęk was possessed by the devil, which is why the wings he had built were not preserved. Because, like any infernal tool, they had to be burned. They vanished into thin air, and nothing was left of them. They were only preserved in the stories of the locals, who kept them alive in their memory. The same goes for Wnęk, except that his bones were lost in the Odporyszów soil for many years. Rumour has it that a forgotten grave was found in the local graveyard a few years ago. The interred skeleton exhibits injuries as if the body that encased it had fallen from high up. People claim that splinters were reportedly found in the bones…

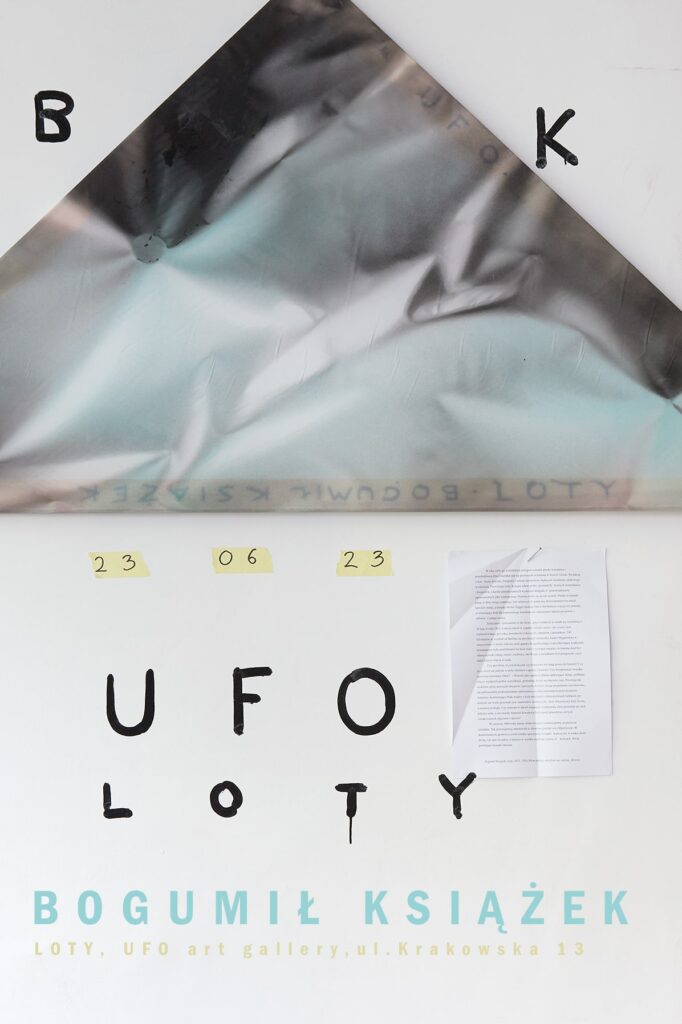

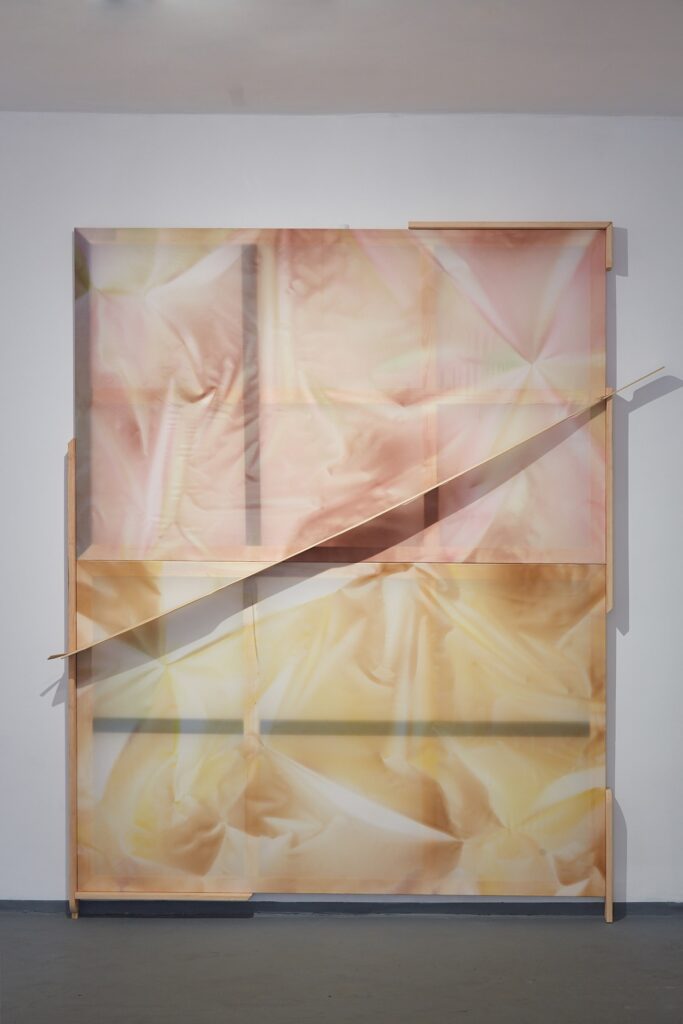

That is all, and history tells us only a little more about Jan Wnęk. The Ethnographic Museum in Kraków possesses a model made in 1956 depicting a rag doll that floats on wings. It is supposedly how Wnęk’s ‘flights’ were remembered by those who saw him fly. One day, this story was unearthed by Bogumił Książek. Did he also once want to fly? As a young boy, did he also build machines that would allow him to soar? I do not know the answers to these questions. What I do know is that at some point, Bogumił began to paint pictures on canvas as delicate as if they were about to fly high into the sky. He applied pieces of wood to them. He would bend them, break them, and arrange them in such a way as to fit them onto the paint-covered canvas best. Sometimes he would encase them in something akin to a wooden frame, a rack of sorts, or a skeleton perhaps? This wooden element made his paintings resemble wings. The dynamics of his paintings, built up by successive wooden slats, boards, sticks, supports, hoops and rods, form into a story inspired by the figure of Jan Wnęk. The lightness of the canvas used by Książek, falling, waving, drifting on the looms hidden underneath, expresses not only the desire to soar into the sky but also the fascination with falling… Towards the ground, even closer to the matter…

Marta Kudelska

In 1891, after many years of preparation, the Prussian inventor and entrepreneur Otto Lilienthal became the first aviator in the history of the world. It is documented by numerous pieces of evidence, photographs, and accounts from authority figures who witnessed the watershed event, the First Flight. The subsequent successful attempts attracted numerous journalists and photographers, and those witnessing the events regarded every second of them as momentous. History was being made before their eyes. With his death on the day of his last flight, the Prussian aviator entered the pantheon of 19th-century heroes of science, and Berlin-Teggel Airport, named after Otto Lilienthal, is more than a monument; it is a perennial tribute to the German designer, punctuated by the rhythm of arrivals and departures from all over the world.

Meanwhile, meanwhile being the wrong word indeed because it is supposed to have happened twenty-four years earlier, in the year 1865, or, instead, in a completely different time – not the time, the Reymont time, the time of seasons, agricultural chores, indulgences and fairs, 700 kilometers east of Berlin, on the outskirts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, in a village where nobody had a camera and the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants were illiterate, someone also challenged nature. The aviator was supposed to be Jan Wnęk, a peasant, carpenter, and sculptor from Odporyszów, and the witnesses were pilgrims, i.e. people who believe in miracles.

Do the peripheries, whether civilisational or cultural, have no right to history? Does life only take place in the range of the camera and camcorder lens? Does the witness’s competence determine the gravity of the fact? History as a science absorbs the days of yore, subjecting accounts of events to the test of verification, gathering evidence of a time gone by. Thus, insightful descriptions of specific areas and certain periods are produced, continually deepened and revised, but at the same time, in opposition to this, peculiar anti-matter wells up proportionately – a contrasting lack of knowledge about these places and human communities, of which little so-called source material remains, although the communities were numerous and the places sprawling. Were the past events in such places, though only echoes and no hard evidence remained, any less real than those tagged with photos and descriptions?

In June 1869, the last attempt, the first unsuccessful one, was finally to come. At least, that is how the village of Odporyszów recorded it in its collective memory. The presumed tomb of the carpenter-aviator holds the remains of a male about 40 years of age, their condition indicative of death due to severe trauma; pieces of wood are embedded in the bones.

Bogumił Książek

Bogumił Książek’s studio is located in Krakow’s Salwator. To get there, you first have to leave the rather busy surroundings of the Old Town and preferably take a tram to the turnback loop near the Norbertine Convent. From there, you must walk and climb St Bronisława Hill towering over the city. This path can be slightly exhausting, as it constantly climbs up the hill, not even for a moment allowing less greedy a breath. This effort, however, is compensated for by the place itself. It is full of sprawling trees with branches protecting picturesque villas separated from the cobbled street by beds of flowers and semi-wild shrubs. For me, this place will forever be fragrant with rose and jasmine buds of May. Bogumił Książek’s workshop is at the end of this road, in a building called the General’s Villa. One of ‘Krakow’s most beautiful modernist villas, designed by a brilliant self-taught architect and built by an egotistical Volksdeutscher, appropriated by a nameless NKVD general, protected better than Bierut,’ the artist explains. For him, it is not an entirely alien territory. As a little boy, he used to run between the trees growing here and must have climbed them, too, to get a better view of the walls of historic Krakow looming on the horizon. Like every child, he probably went on expeditions to places that must remain a mystery in the adult world.

When I look at Książek’s paintings, I think that not only his inspirations, fascinations and life experience are contained in them somewhere, but underneath the layer of paint, there is this Salwatorian uncanniness. In a conversation with Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec, he admitted that his own experiences are closely correlated with what he paints. ‘They determine everything. I wouldn’t be able to function otherwise. Someone once said the view from a childhood window later projects itself onto the painter’s work. I grew up on a balcony overlooking the Vistula, the Tatra Mountains, Kościuszko’s Mound and Krak’s Mound, and – peeping around the corner – Wawel.’ He went on to add that in Kraków’s Salwator, ‘instead of in everyday life, one always lived in a world of Salwator stories.’ However, it is difficult to search in his paintings for simple illustrativeness, which would manifest itself in visualizations of the stories he knows. Instead, Bogumił Książek’s painting is close to the convention of magic realism, although this is also an oversimplification. It is homely, ordinary, yet sometimes surreal elements appear. However, thinking these are invented characters or stories would be wrong.

For in the world that surrounds him, Bogumił Książek searches for myths, fairy tales, legends, and traces of ancient beliefs that create our reality to the same extent as science or technology create our reality. With undisguised fascination, he weaves his way through pages of books, searching through old magazines, digging forgotten stories out of oblivion. He searches, tracks, seeks to understand, and then begins to paint.

‘The paintings always follow me for some time before I start painting them. Then I discover a story, and it turns out that one and the other were looking for each other,’ explains the artist.

After graduation, this penchant for adventure and discovering the stories that shape our worldview led him to Tuscany. Yet, before indulging in views taken straight from the canvas of the Renaissance painters, he studied painting at Krakow’s Academy of Fine Arts in the studio of Sławomir Karpowicz and philosophy at the Jagiellonian University. Jagiellonian University. For a while, with a group of friends, he also ran the independent gallery Pod Ręką.

As he himself admits, ‘I landed in Italy by a redemptive coincidence that changed everything. I want to point out that I do not believe in coincidences. I go back there every day with my thoughts.’ In Italy he became fascinated by the work of artists such as Pierre Pizzi Cannella and Mario Sironi. They joined his painterly fascinations: Mimmo Paladini, Albert Oehlen, Sigmar Polke. Książek draws from them an austerity of painterly expression but also a sensitivity to colour and a sense of observation of the surrounding world.

At first glance, the structure of his paintings appears simple. However, the longer we look at them, the more they begin to open up before us, like rooms in a house forgotten by the world. A different story awaits us in each of them, a different tale. Reading his paintings is somewhat akin to wandering through a fairy-tale labyrinth, where something new is hiding behind every corner, turn, or bend. However, just as in fairy tales, it is only up to us if we pay attention to these stories, follow them further and get lost in yet another thicket of interpretation. Bogumił, however, leaves us with small clues that make it easier for us to navigate through the stories he paints. Sometimes they refer to what is no longer there, while others draw on the here and now. Książek leaves us small traces that make it easier for us to decipher the riddles he leaves behind. Sometimes it is details that can lead us to a clue: a specific, delicate canvas, a curved frame, the characteristic position of a figure’s hands, an outline barely visible against a background of vibrant colours. Bogumił Książek’s painting teaches us mindfulness: of the world, its stories, and ourselves.

Marta Kudelska