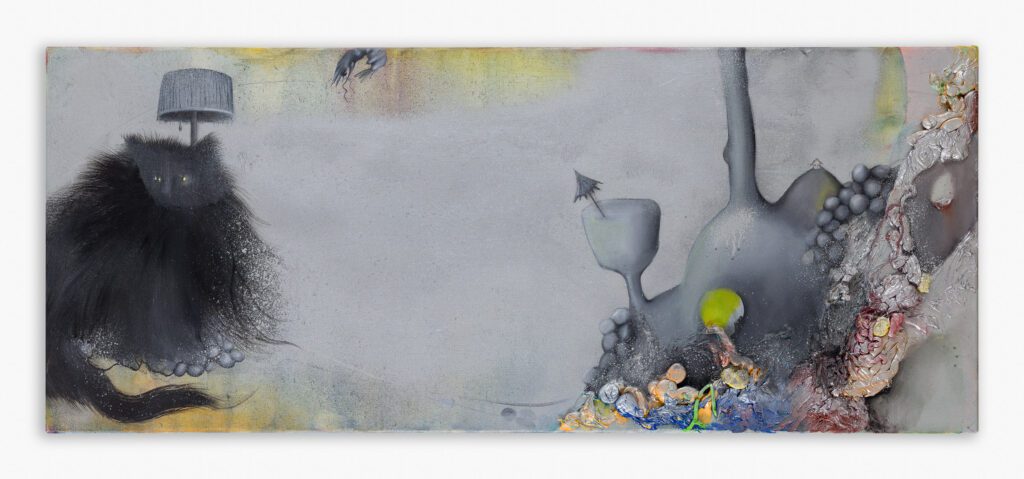

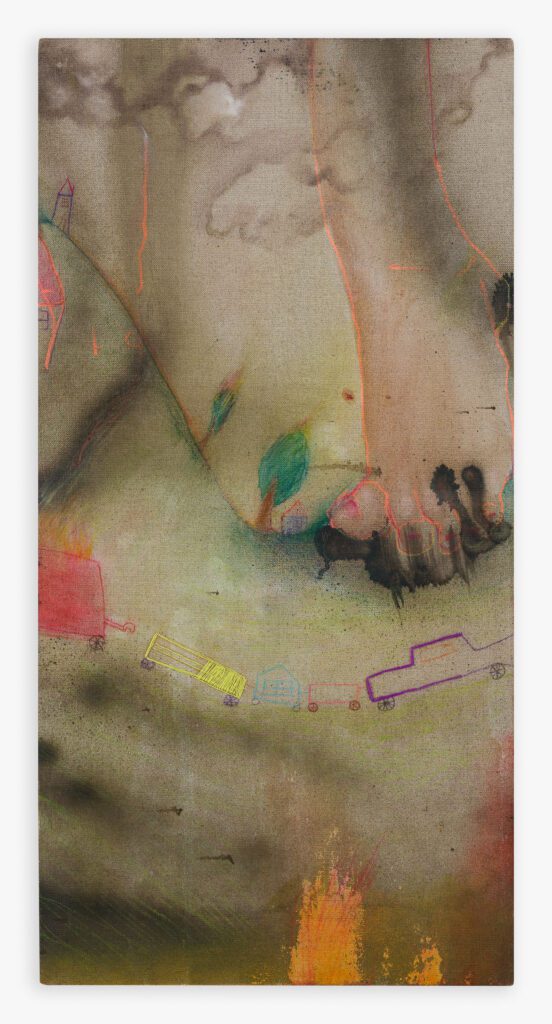

‘No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.’1 With this statement, Shirley Jackson opens the plot of The Haunting of Hill House. Dreams, including daydreams, allow one to take root in the world. They are not an expression of languid, exaggerated aestheticism but serve an important function in finding one’s axis mundi, one’s point of reference. They work well as life maps, verifying a sense of well-being. Sometimes, it is the people who belong to a place; a permanent bond with it is sometimes the basis of individuality. Some territories choose people, catch them in a net. This is why one of the most important dreams concerns the home. Understanding and defining space, including the primary, safe space, is crucial to my creative process. I set thresholds. I look for rituals of transition between inside and outside.

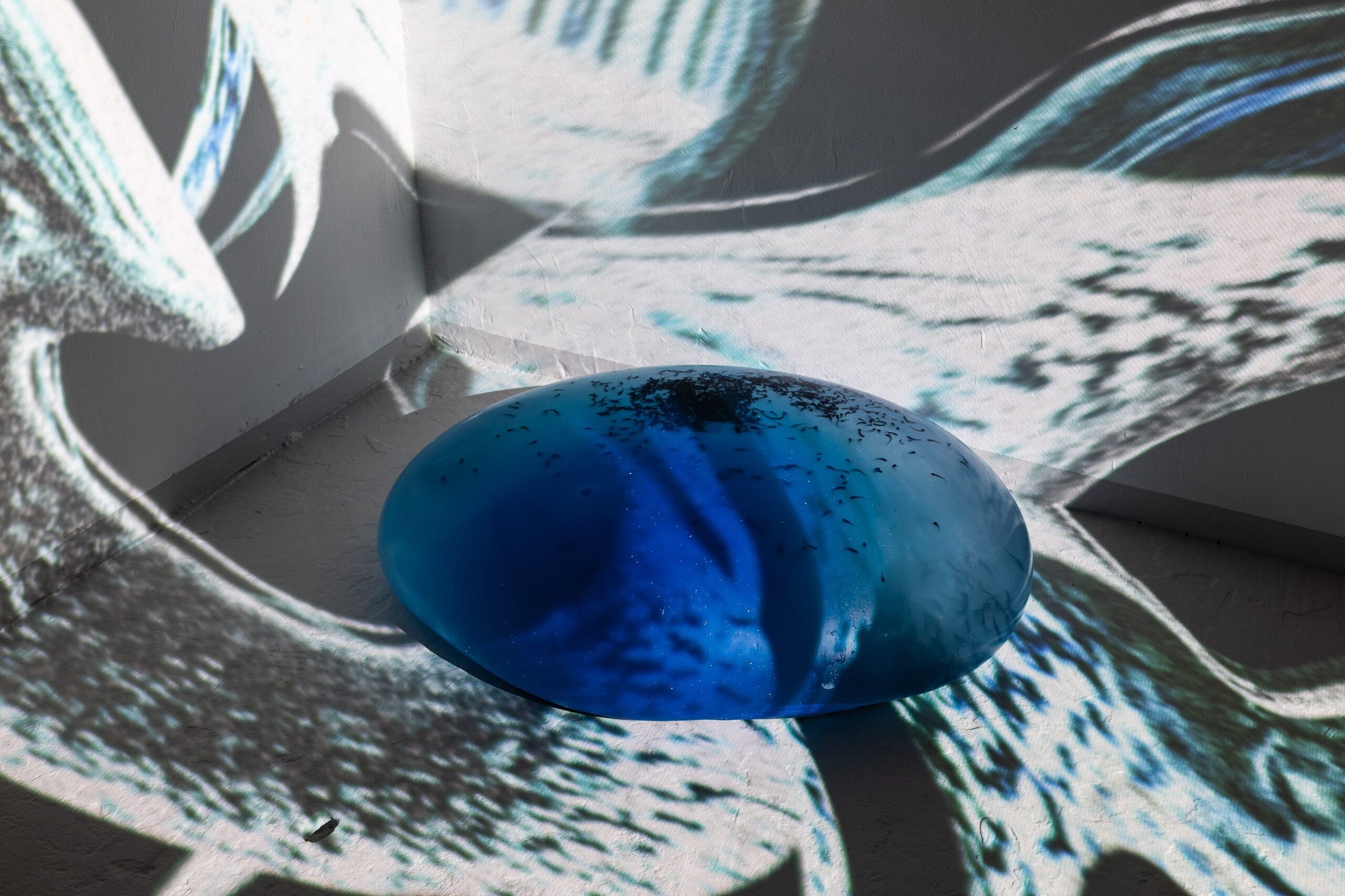

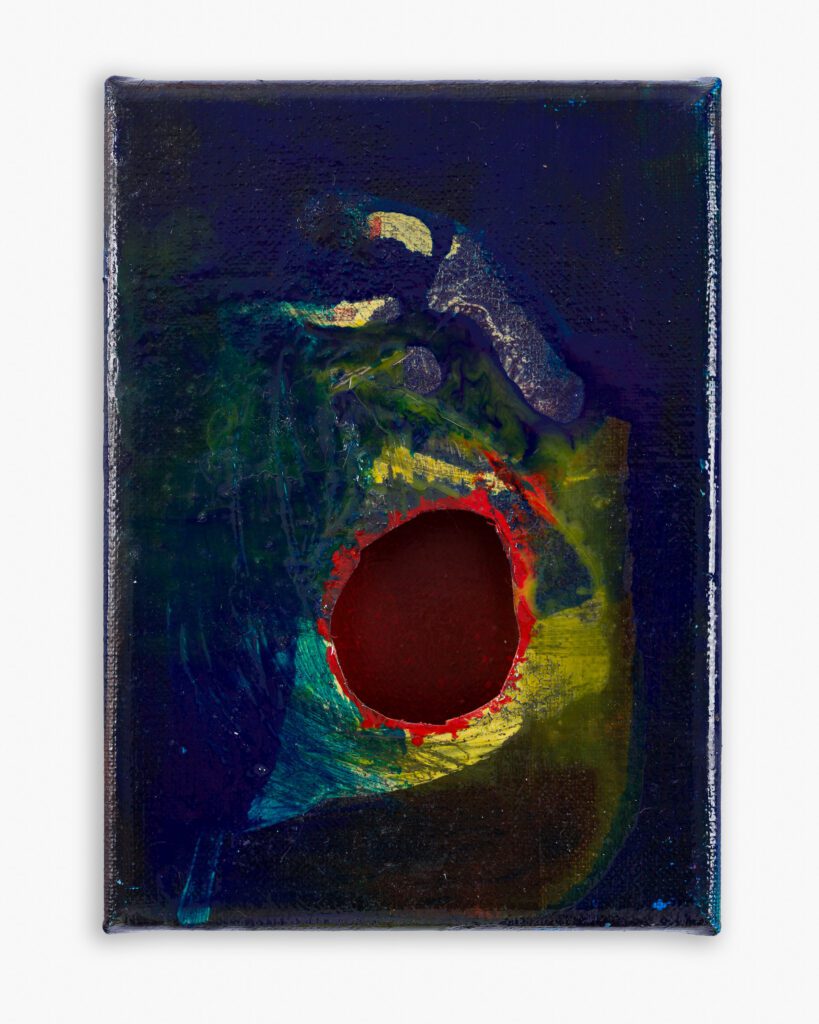

Carl Gustav Jung came up with the idea of the difference between the collective and individual unconscious through daydreaming about a house. The old, lower floors symbolised collective experience, while the higher floors were associated with a specific subject, himself. Victoria and I used Jungian dream analysis to work on the exhibition. All this because I often dream about other people’s houses, buildings I have never been in. I rarely find attics in my houses, but there are usuall cellars, sometimes filled with water. In water, the promise of life is balanced by the threat of death. I am close to the poetics of the myths of mermaids, selkies, and water nymphs. I’m not afraid of diving; I’m not afraid of going down; I’m drawn underwater; I go very deep, into the dark lakes, the impenetrable depths. Those are interesting places; that’s where the mystery of life is. That’s where I feel comfortable. I am rather more afraid of open spaces. In my dreams, I often fight against regimes. Recently, I dreamt of a Western movie. People on horses were chasing me. I jumped into the sea, found a circular entrance and entered a bubble. It was an underwater world ruled by a regime. I had an affair with a bloke who worked for the regime, but then he changed and helped me and the opposition. I managed to find another hatch from the underwater world because the first one was closed. Thanks to me, people started to escape from the bubble; I realised I couldn’t win against the regime, but I could let them out. I swam from the underwater world into the water and saw ancient Greek ruins, and then suddenly, I was in a modern city.

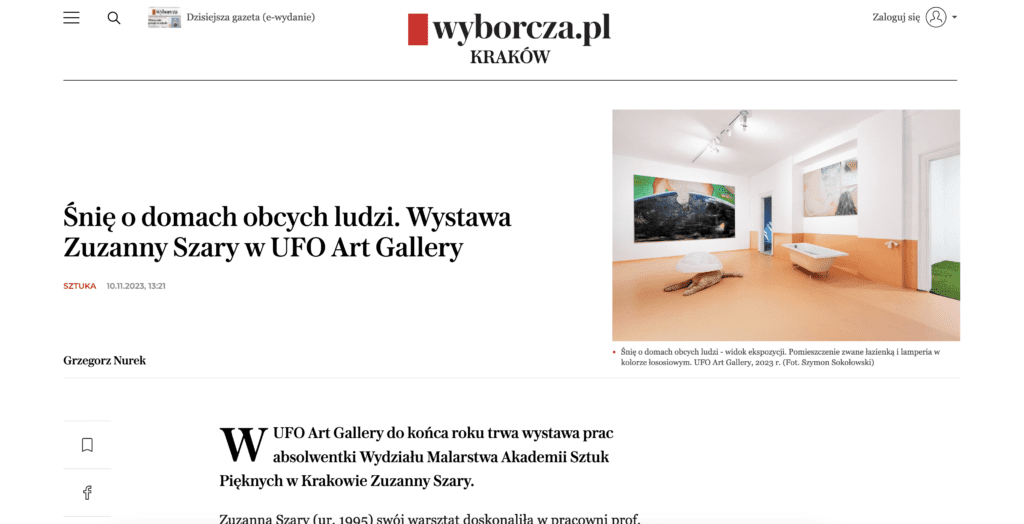

I usually settle in the houses belonging to strangers in the next dream. The middle part of the houses is the most elaborate. I keep dreaming that I am starting to live with a group of strangers. My house has many rooms, and its meandering layout expands and swells with each successive dream. In a situation of imbalance, my house changes from a bastion of safety to a source of danger, a Schulzian labyrinth, a Dark House. Space arrangements move and live their own lives, as in the recent film adaptation of Jackson’s novel. ‘Silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.’2 So ends the story.

Wiktoria Kozioł and Zuzanna Szary

Collaboration: Kinga Kociarz (turtle object), Emilia Ishizaka (mapping)