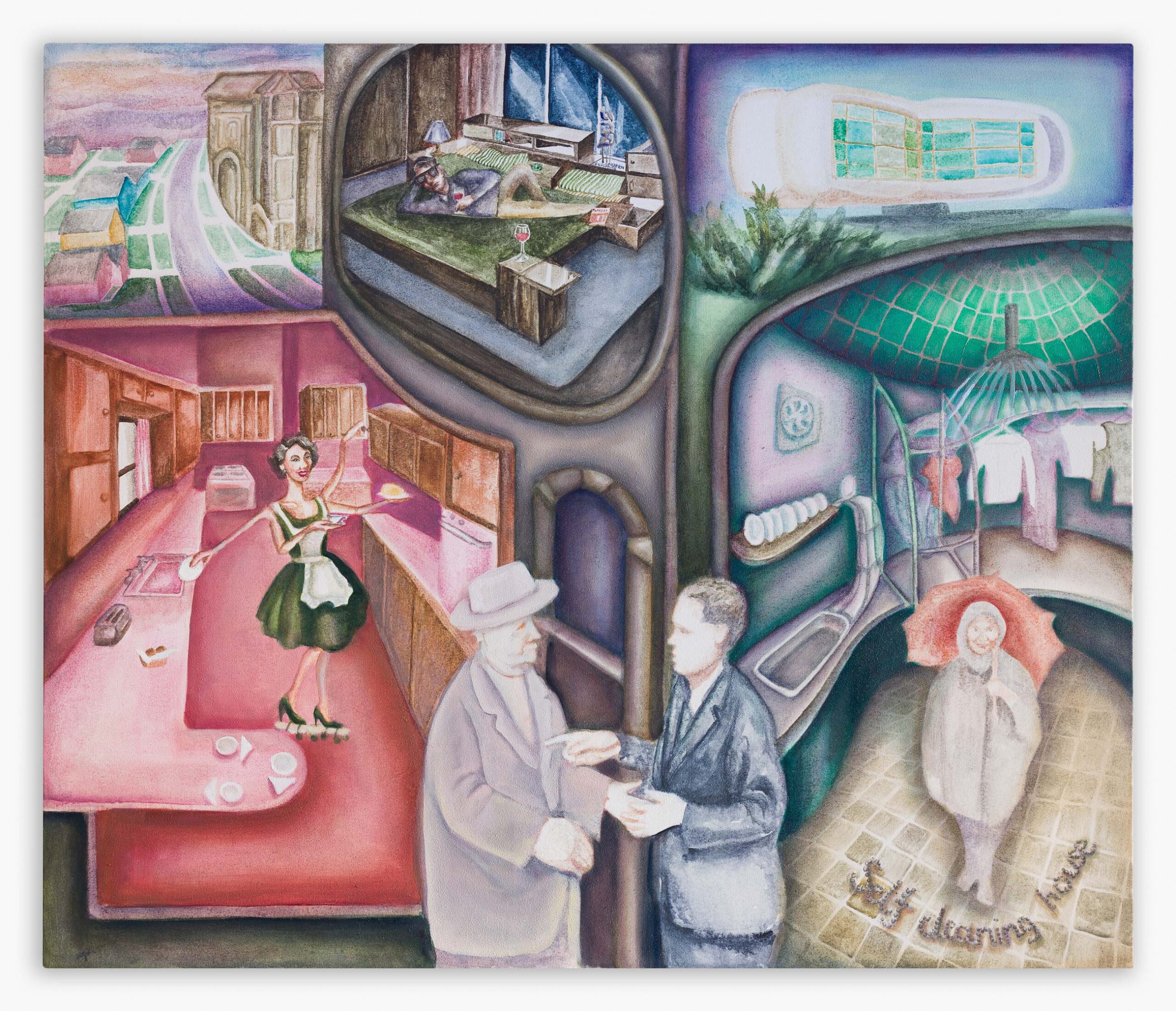

I was interested in the intersection of critiques from post-work theory (which reflects on potential forms of reorganizing societies in relation to the forms and scope of paid labor) with urban and architectural projects that were intended to address social needs by introducing efficiencies in the realm of housework. This image is a collection of vignettes illustrating various historical solutions. The starting point for the image was housing schemes aimed at supporting the reorganization of and/or reducing the amount of unpaid domestic labor performed by women in the developed Global North.

The first example is a single-family suburban home from the 1950s, equipped with the latest technological marvels: ovens, microwaves, and washing machines. As architectural historian Dolores Hayden points out, the ideal of the home replaced the ideal city in the American collective imagination, which had previously served as the reference point for spatial representations of the good life. Contemporary advertisements for household appliances develop a specific techno-fantasy whereby modern home devices rescue women from daily drudgery, transforming former duties into satisfying and effortless tasks. Hence the elegant housewife speeding by on roller skates to finish in time before her husband returns from work.

A diametrically different vision of living space was offered by the first studio apartments, essentially designed with the needs of young, affluent, unmarried men in mind. The layouts and ways these apartments were organized are well documented in the early issues of Playboy magazine. Tellingly, the kitchen was almost entirely eliminated from this space, with only a token bar at which the bachelor could impress invited dates with his ability to prepare striking cocktails. The central and most important piece of furniture was, of course, an expansive bed.

In the late 1960s, more spectacular and futuristic ideas for organizing domestic space began to appear (such as the glass-walled house in the upper right corner). Furniture projects in the speculative design vein—resembling a space-age home out of The Jetsons—captured the collective imagination of the American middle class. Nevertheless, despite their seemingly modern appearance, they were still conceived as isolated, contextless units primarily intended for the celebration of intensified consumption.

There were also surprising, genuinely innovative visions that did not stand the test of time. The inventor Francis Gabe, whom I portrayed inside her home under an umbrella, designed and single-handedly built a self-cleaning house. Gabe was an engineer who, after her divorce, decided to eliminate domestic drudgery from her life once and for all. She introduced various systems of improvement into her home: the dishes washed themselves and were then transported to the cupboards. A ceiling-mounted sprinkler sprayed surfaces with water mixed with detergent, followed by clean water (all of the upholstery in Francis Gabe’s home was made of waterproof fabrics). When asked what motivated her to devise and implement such an elaborate system, Gabe always replied that life is too short to waste it on cleaning.

The central part of the image features two male figures, the participants in the titular Kitchen Debate: Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev. The term has come to denote their heated exchange of views on how to arrange domestic interiors, an exchange that was highly representative of Cold War tensions. In Moscow in 1958, an exhibition was organized to showcase the latest American-made household appliances intended to streamline housework. After viewing the model of an American kitchen, Khrushchev began to mock Americans, whom he believed fetishized consumer goods of poor quality and durability. Nixon emphasized values such as individualism and expanded possibilities for consumer choice. In my view, this event not only illustrates a confrontation between two antagonistic visions of social organization. For me, the Kitchen Debate is also a story about what the political dimension of domestic space can entail.